Rising indebtedness has elevated concerns about the ability of borrowers to cope with economic stress.

Rising indebtedness has elevated concerns about the ability of borrowers to cope with economic stress.

The Bank of Canada (BoC) weighed in on this topic last week. In its semi-annual Financial System Review, the BoC performed a variety of simulations to estimate how job losses and rate hikes might prevent some people from paying their mortgage.

Here are some of its findings:

(Quotes belong to the Bank. Italics are ours.)

Risk Factors

- “Households remain exposed to interest rate risk.” However, the biggest damage to “vulnerable households” would come from “a significant decline in house prices” and/or “a sharp deterioration in labour market conditions,” both of which are inter-related.

- Housing assets now account for about 40% of Canadians’ net worth, up from 34% 10 years ago.

(This reinforces the necessity of a soft landing in real estate—which depends on a host of factors, including interest rates, growth in housing inventory, lending policy, and so on.)

Vulnerable Consumers

- 6% of indebted households have a total debt service ratio of ≥ 40%. Those households owe about 7% of all outstanding debt.

(The BoC notes that both of these proportions have remained above their 2002–11 averages, despite record-low interest rates.) - Under the Bank’s hypothetical rate scenario (in which rates rise 325 points by mid-2015 and households do not reduce their exposure to higher rates), households with a debt-service ratio ≥ 40% would go from holding 11.5% of total debt in 2011 to holding 20% by 2016.

Mortgage Arrears

- Here’s a table showing how soaring unemployment and interest rates could potentially impact mortgage arrears, according to BoC simulations:

|

(The worst case in this table would be a 400 bps rate hike coupled with a 6 percentage point jump in unemployment. That would trigger 195 basis points of arrears, compared to the current level of 35 bps.

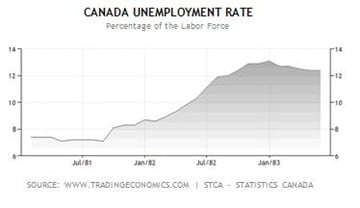

Anything north of 1% arrears would be extreme. The modern-day record was 1.02% in 1983, according to CMHC.

Note that a 6% jump in unemployment was what Canada faced in 1982, as seen in the chart below. That coincided with serious stagflation, however, which is a low-probability event in this era.)

- The BoC’s arrears models do not assume that distressed households will sell their homes to avoid default. That’s slightly unrealistic since selling to avoid foreclosure does mitigate some arrears—the extent of which depends on how easily people can sell in a weak/falling market.

Steve Huebl & Rob McLister, CMT

Plan for the worst and hope for the best

>400 bps rate hike coupled with a 6 percentage point jump in unemployment. That would trigger 195 basis points of arrears,

Can you explain how you arrived at that number? The intersection says 290 bp. Thanks.

from a baseline of 35bps current arrears, if unemployment jumps 2% the INCREASE would be 85 bps bringing us to a total of 1.1% total arrears rate which as per the author would be extreme and exceed the previous 1982 record.

am i reading this right? i sure hope not, because otherwise we may as well start packing our bags.

IMO a 2% increase in unemployment is just about a given at this stage…

And while the BoC and every quant freak economist formulates useless micro-equations to forecast the decision of every small business and corporate CEO, here is one useful statistic (one that matters) of Toronto’s employment rate. http://postimage.org/image/6r1nui9dt/

There is nothing central banks can do at this point (without losing their credibility) that can save the economy, when it is ‘less’ central bank and government intervention that restores economic equilibrium.

One day the broker community will realize they should have been encouraging higher rates for the sake of their own jobs. I guess they’ll never know until major problems materialize. Then it’s too late.

Hi emmi,

It’s a 290% increase, not a 290 bps increase.

The Bank of Canada is using a 0.5% arrears rate as its base for this estimate.

Cheers…

Hi EMB,

If the current 0.35% arrears rate jumped 85% (it’s percent, not basis points) it would bring arrears to 0.65%. That’s based on the Canadian Bankers Association measure.

That would match the peak arrears seen in 1997 and 1992, but nonetheless be controllable.

Cheers…

ah i see. that’s somewhat reassuring. it’d take a number closer to 200% increase in the baseline (.5% according to the chart) arrears rate for us to be at 1982 levels. at least that leaves room for BOC to mitigate by keeping rates low if unemployment gets out of hand.

OK, I’ll bite. How do higher rates help mortgage professionals?

Thanks. That’s confusing given the scales are so similar to the column labels.

Except it the bond market gets out of hand…

Exactly how much control do you think brokers have when it comes to determining market interest rates?